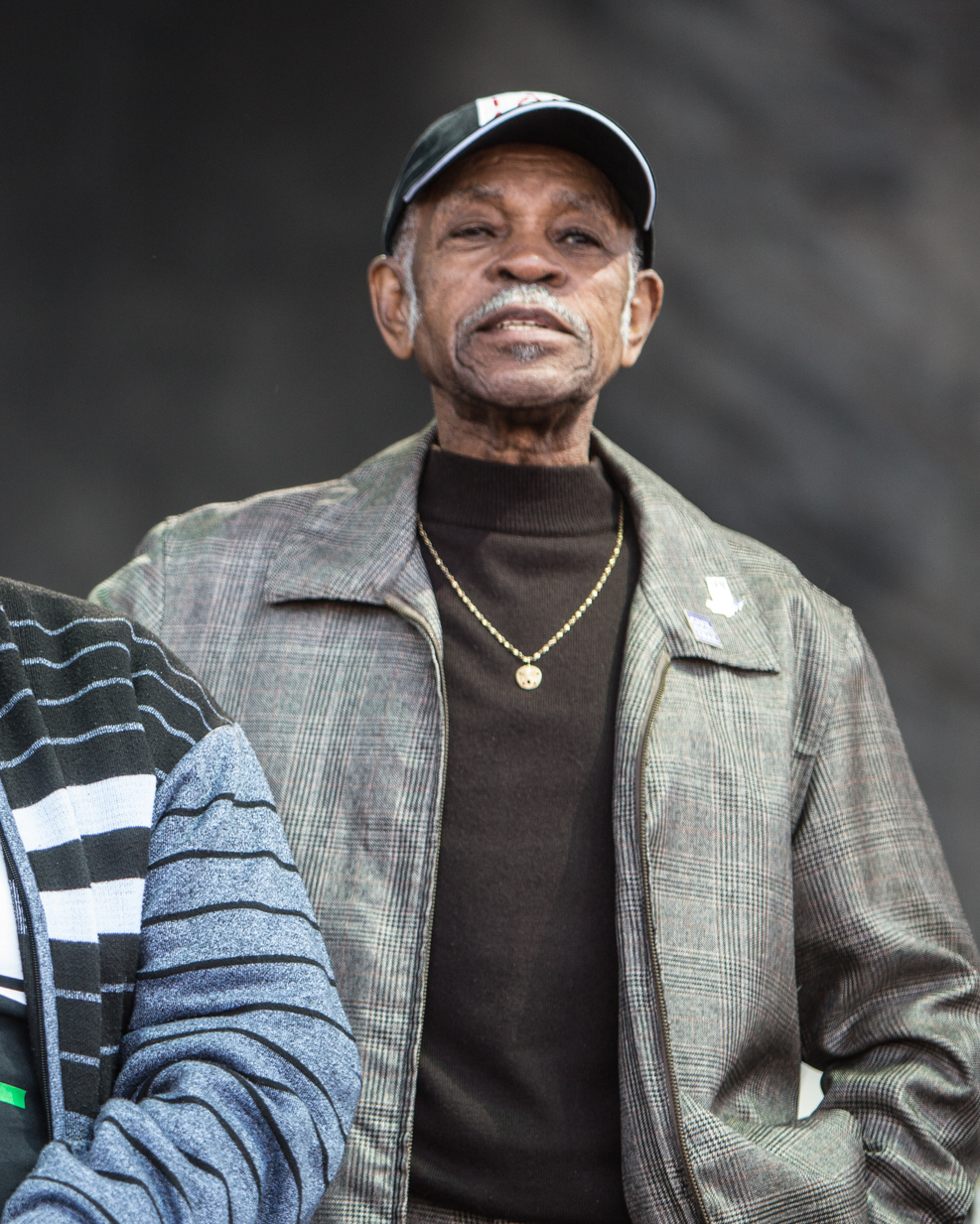

Elmore Nickleberry, one of the original AFSCME sanitation workers who went on strike in 1968 to fight for fair wages, safer worker conditions, union recognition and dignity, has died in Memphis at age 92.

Nickleberry was one of nearly 1,300 mostly black sanitation workers in Memphis who endured grueling, unsafe working conditions and poverty wages ($1.65 a day) in the 1960s. He was one of the last of the original strikers.

He described what it was like to tote the heavy garbage bins over his head: “Sometimes the tub had holes in it, and garbage would run all down my face — maggots and stuff all in my face.” He said that at the end of the day, he smelled so bad he was not even allowed on city buses.

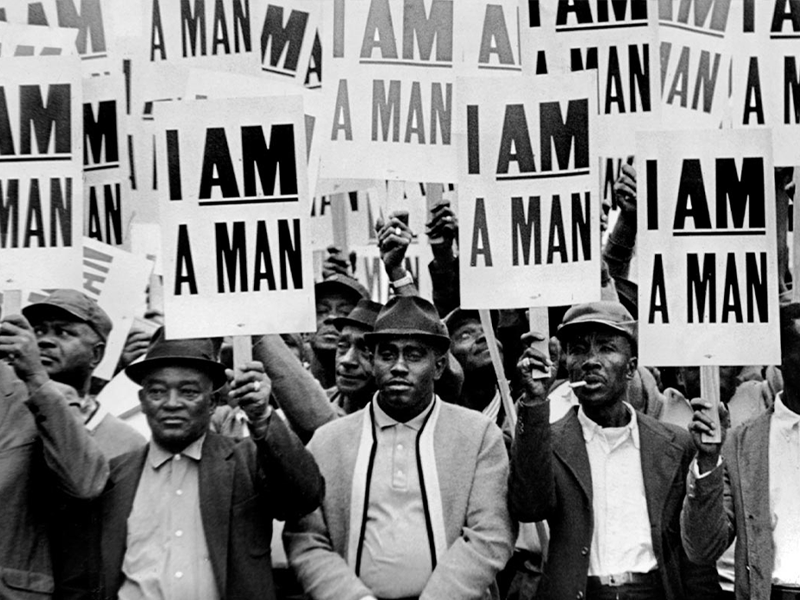

The workers’ longstanding fight for union recognition came to a head in the winter of 1968, after two sanitation workers, Echol Cole and Robert Walker, were killed in the malfunctioning compactor their garbage truck.

Their deaths led Nickleberry and his fellow sanitation workers to go on strike, braving tear gas and police brutality. They were joined in their strike by labor and faith leaders, including the Rev. Martin Luther King. Jr., who was killed in Memphis in April 1968 on a visit to support the strikers and their cause.

The workers’ would go on to win their fight for union recognition, better wages and working conditions, and Nickleberry would go on to work for the City of Memphis for more than 60 years. He was still working at 86 years of age.

In 2017, the City of Memphis provided Nickleberry and the other surviving strikers (there were 13 at the time) with grants of $50,000 each, in order to allow them to retire. He was the longest serving Memphis city employee.

As for the iconic strike and the wider movement he was a part of, Nickleberry told the New York Times: “We have made some good progress, but there can still be more progress made.”